Greyson Quarles took nearly 14 hours to complete his first Ironman Triathlon in early 2000, not a particularly good time, but he felt proud anyway. After all, he did it less than a year after one of Harvard’s finest orthopedic surgeons took apart his left knee and reassembled it at a whole new angle atop his lower leg.

Quarles’s surgery was expensive, debilitating, and included a then-unproven variation on cartilage repair. That didn’t bother him, however. Certainly not as much as the thought that, without surgery, he wouldn’t be able to walk out the door three or four times a week and simply start running. That’s what Quarles had been doing for several decades, and that’s what he wanted to continue doing. “My tombstone won’t say ‘CPA’ or ‘CFO,’ ” says Quarles, an executive vice president and the chief administrative officer at SAS, the statistical software giant. “It’ll say, ‘triathlete.’ Running is my passion.”

Quarles’s passion is the simplest and purest of all sports, which probably explains its widespread popularity. To enjoy running, you need little more than a good pair of shoes. Of course, it also takes a decent pair of knees, and that’s where the problems sometimes begin. Studies show that anywhere from 30 to 60 percent of runners get injured every year, and 30 to 50 percent of those injuries strike the knees and surrounding tissues.

Anterior knee pain. Patellofemoral pain. Chondromalacia. Iliotibial band syndrome. No doubt about it, the knee is a cranky little thing. You need only look at it to see why, and how it differs from the body’s other major joints. The shoulder consists of a huge capsular contraption that holds the bones in place. The hip, too, is built like a suction cup. No such deep-fitting sockets for the knee, which swings almost like a hinge on a gate. But as the knee swings, it pivots to accommodate a thigh bone that’s longer by design on one side than the other. Every flexion and extension and simultaneous rotation pulls into play four major ligaments that strap the joint together, some of them passing right through its center. No wonder it sometimes it gets sore or swollen–or worse.We’re in the midst of a knee crisis, says Brian Halpern, M.D., a sports-injury specialist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York and author of the just-released The Knee Crisis Handbook. The knee held the No. 1 spot in a notorious top-10 list last year [“The Comprehensive Study of Sports Injuries in the United States,” by American Sports Data, Inc.], beating out every other body part for the greatest number of sports injuries, according to a survey of more than 15,000 households.

Fortunately, for all its complexity, the knee is well designed to perform its most basic function–allowing you to walk and run in a straight line. Every fitness and medical expert recommends brisk walking as a great exercise routine, and a long-term study of the 50-Plus Runners Association of Stanford University has revealed that its 70- and 80- and 90-year-old members have few arthritis and joint pains. Fewer than nonrunners, in fact.

That said, no one can deny that runners get knee injuries, sometimes from physical differences that are difficult to control, and sometimes from personal training habits that we should monitor more closely.

High arches and low ones. Bow legs and knock knees. Too little strengthening. Too little stretching. Too many miles. Too many hills. And those are just the major culprits. Another one: the huge number of strides that a runner takes in a week, month, year–about 1,400 per mile. Each stride sends a jolt up your legs and through your knees.

“Think of running as a series of collisions with the ground,” says Stephen Messier, Ph.D., a runner and orthotics researcher at Wake Forest University. (An important note: Those jolts also have a very positive effect. They build strong bones. Athletes in nonimpact sports, such as swimming, don’t show the same bone-building propensity that runners have.)

When you walk, a force equivalent to several times your weight travels up your leg with each heel-strike. When you run, the shock forces increase. Yet running researchers tend to be running researchers, and while they recognize the price they may pay for enjoying their chosen sport, they don’t see it as a reason to quit. There’s no perfect training formula, but Messier, Dr. Halpern, and other knee experts believe runners can keep themselves sound–if they pay attention to their bodies and run at a level that’s appropriate for them. Messier and his colleagues at Wake Forest University have conducted laboratory tests on hundreds of injured and uninjured subjects, measuring leg length and arch height, videotaping the flexion of the foot milliseconds after heel-strike, testing muscle strength, and collecting countless other pieces of data. “The problem is there are so many variables when it comes to the way people run,” Messier says. “It drives our statistician crazy.” Their years of lab study have not yielded simple answers; they’re still not able to draw a straight line between a particular body configuration and a running injury. But they have gleaned lots of clues about ways that runners can usually fix the problems that the sport engenders, or avoid them in the first place.

At the crux of many runners’ knee problems is the intersection of the kneecap (also known as the patella) with the thighbone (a.k.a. the femur). As the leg extends, the kneecap travels up and over the end of the thighbone.

But if things don’t work as intended, “It’s like driving with your tires out of alignment,” says orthopedist Stan James, M.D., who consulted with Nike on some of its early running shoes and performed knee surgery on many famous runners, including Joan Samuelson. “If they’re just a little out of alignment, it probably won’t do too much damage. But if they’re severely out of alignment, you’re not going to drive very far before you need a new set of tires.”

As your kneecap rubs against the cartilage in your knee, the friction causes a painful inflammation. The burning, achy sensation under and around the kneecap is known as anterior knee pain or patello-femoral syndrome.

This is not something to ignore, and you should never allow pain and inflammation of the cartilage on the underside of the knee to continue for long. If it does, you may develop chondromalacia, a much-abused term that’s often used for anterior knee pain. It means the cartilage under your kneecap has gotten rough and started to soften. (You may even hear a Rice Krispies crackle when you flex or extend your knee.) If you develop bona fide chondromalacia, you face the threat of arthritis in your future.

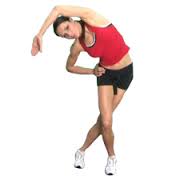

Another problem common among runners is the stabbing pain of a tight iliotibial band. This thick band of tissues runs from the pelvis along the outside of the leg, attaching to the shin just below the knee. It has to clear the knobby end of the thighbone with every step–or, if it’s too tight, scrape its way over the protrusion. Typically, the friction doesn’t become irritating until a few miles into a run, but when it does, it can be major-league pain called iliotibial band syndrome, or ITBS.The best way to protect your knees is with daily stretching and strengthening exercises, and the easiest way to stick to your daily program is to do the exercises at home without any special equipment. Here we show the two best, simplest home exercises to keep your knees in top shape.

ITB Stretch

Stand with one leg in front of and crossed over the other leg. Exhale, and bend your body to the same side as your front leg. Hold for a count of 20, straighten up, then repeat the bend nine more times. Reverse leg positions, and repeat 10 times in the other direction.

Quadriceps Strengthener

With your feet side-by-side, extend both arms forward, and slowly lower yourself into a half-squat, stopping before your legs are parallel to the ground. Keep your back straight. Repeat 20 times.Adapted from The Knee Crisis Handbook,–Brian Halpern, M.D.Burning inflammation, piercing pain: To avoid them, first consider a likely culprit: your shoes. If your heel counters tilt noticeably to the medial (arch) side, you’re probably an overpronator, and the inward movement of your foot twists your heel counters out of shape. Sports medicine specialists have long assumed that the resulting torque on your shinbone would pull the kneecap off-center, setting you up for runner’s knee. It’s not so simple, Messier says. In his studies, injured runners are no more likely to overpronate than healthy ones. Still, his tests suggest there are subtle differences in the motion of the injured runner’s foot as it flattens and then rolls toward push-off, so it makes sense for you to deal with this excess rearfoot motion.Most of the time that’s easily accomplished with a good pair of motion-control shoes, Messier says. (Check out our quarterly Runner’s World Shoe Buyer’s Guides, or go to runnersworld.com for our online reviews.) An inexpensive drugstore arch support may also help. (Runners with flat feet often overpronate, though your feet may not look flat except when they hit the ground.) Or you may need a customized orthotic–a prescription corrective shoe insert made by taking a cast of your foot.

If your feet aren’t flat, you’re not necessarily in the clear. Many injured runners in Messier’s studies had relatively high arches. A high arch makes for a rigid foot, one that may not absorb as much impact as a more flexible foot. If you have high arches, Messier and other medical experts recommend you wear a more cushioned shoe, which will reduce forces on your feet, knees, hips, and back.

See full story on runnersworld.com

Image courtesy of runnersworld.com