Fractures are common: most people will experience at least one during a lifetime. With modern medical and surgical care most heal without problems or significant loss of function. However, fractures are associated with a range of complications. Acute complications are generally those occurring as a result of the initial trauma and include neurovascular and soft tissue damage, blood loss and localised contamination and infection. Delayed complications may occur after treatment or as a result of initial treatment and may include malunion, embolic complications, osteomyelitis and loss of function.

The risk of complications varies with the particular fracture, its site, circumstances and complexity, with the quality of management, with patient-specific risk factors such as age and comorbidities, and with post-fracture activities such as air travel and immobility.

Risk factors

Fracture complications are often variably defined, and there is a lack of consensus in their assessment, which makes their incidence difficult to estimate. Complications clearly vary with fracture site and nature and with quality of surgery but many also vary with patient attributes such as age, nutritional status, smoking status and alcohol use. A retrospective study using the UK GP Research Database identified the main risk factors for healing complications (delayed union, non-union or malunion), regardless of fracture site, as:

- Diabetes (type 1 or type 2).

- Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) within 12 months.

- A recent motor vehicle accident (one month or less prior to fracture).

- Oestrogen-containing hormone therapy (although this may be a proxy for osteoporosis).

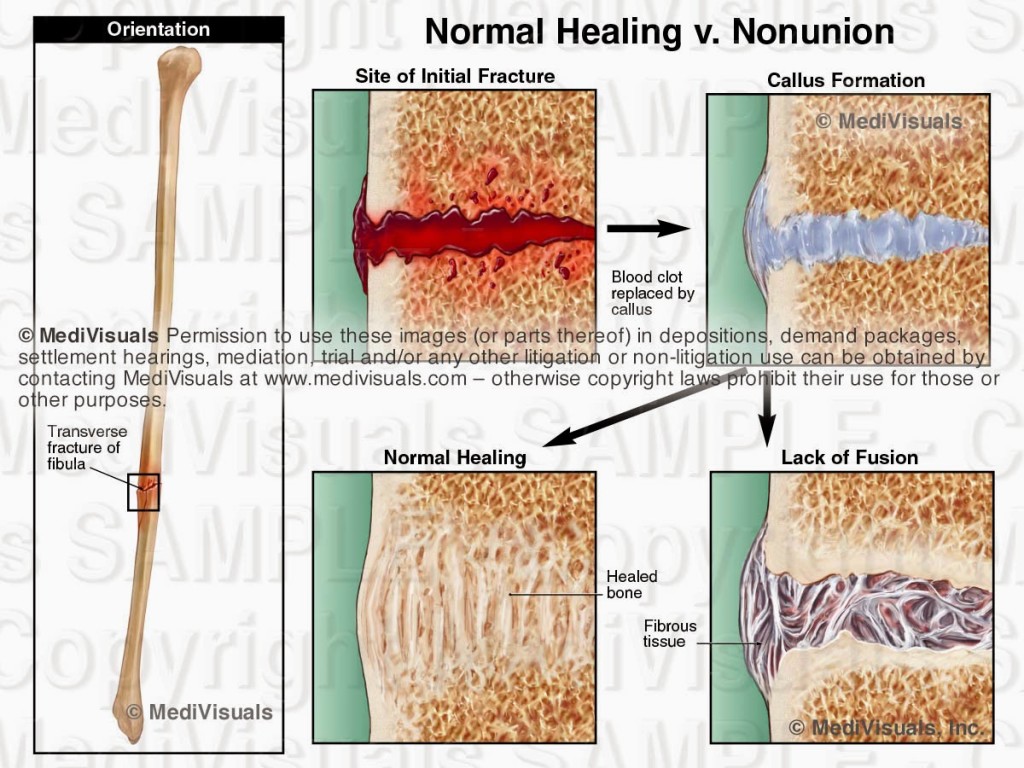

Normal fracture healing

The process of normal fracture healing involves:

- Inflammation – with swelling, lasting 2-3 weeks.

- Soft callus formation – a decrease in swelling as new bone formation begins, fracture site stiffens. This takes until week 4-8 post-injury and is not visible on X-ray.

- Hard callus formation as new bone bridges the fracture site. This is visible on X-ray and should fill the fracture by weeks 8-12 post-injury

- Bone remodelling – the bone remodels to correct deformities in the shape and loading strength. This can take several years, depending on the site.

For healing to happen the site needs adequate stability, a blood supply and adequate nutrition. Healing rates vary by person, and are likely to be compromised by the risk factors above and by age and comorbidity.

Fracture complications such as excessive bleeding or soft tissue compromise, infection , neurovascular injury, presence of complex bone injury, such as crushing or splintering, and severe soft tissue trauma will clearly prolong and possibly hinder or prevent this healing process.

Early complications

Life-threatening complications

- These include vascular damage such as disruption to the femoral artery or its major branches by femoral fracture, damage to the pelvic arteries by pelvic fracture.

- Patients with multiple rib fractures may develop pneumothorax, flail chest and respiratory compromise.

- Hip fractures, particularly in elderly patients, lead to loss of mobility which may result in pneumonia, thromboembolic disease or rhabdomyolysis.

Local

- Vascular injury.

- Visceral injury causing damage to structures such as the brain, lung or bladder.

- Damage to surrounding tissue, nerves or skin.

- Haemarthrosis.

- Compartment syndrome (or Volkmann’s ischaemia).

- Wound Infection – more common for open fractures.

- Fracture blisters.

Systemic

- Fat embolism.

- Shock.

- Thromboembolism (pulmonary or venous).

- Exacerbation of underlying diseases such as diabetes or coronary artery disease (CAD).

- Pneumonia.

Fracture blisters

These are a relatively uncommon complication of fractures (2.9% of fractures admitted to hospital in one series) in areas where skin adheres tightly to bone with little intervening soft tissue cushioning. Examples include the ankle, wrist, elbow and foot.

Fracture blisters form over the fracture site and alter management and repair, often necessitating early cast removal and immobilisation by bed rest with limb elevation. They are believed to result from large strains applied to the skin during the initial fracture deformation, and they resemble second-degree burns rather than friction blisters. They may be clear or haemorrhagic, and they may lead to chronic ulcers and infection, with scarring on eventual healing. Management involves delay in surgical intervention and casting. Silver sulfadiazine seemed in one review to promote re-epithelialisation.[2]

Risk factors, other than site, include any condition which predisposes to poor skin healing, including diabetes, hypertension, smoking, alcohol excess and peripheral vascular disease.[3]

Late complications of fractures

Local

- Delayed union (fracture takes longer than normal to heal).

- Malunion (fracture does not heal in normal alignment).

- Non-union (fracture does not heal).

- Joint stiffness.

- Contractures.

- Myositis ossificans.

- Avascular necrosis.

- Algodystrophy (or Sudeck’s atrophy).

- Osteomyelitis.

- Growth disturbance or deformity.

Systemic

- Gangrene, tetanus, septicaemia.

- Fear of mobilising.

See full story on patient.info

Image courtesy of patient.info